So, last time we went over all the vowels in the Bengali script. We covered a handful of consonants along the way, but now we’re heading into the thick of it, and going through the first major round of consonant sounds.

I didn’t highlight it last time, but the characters in the Bangla script have an order in which they’re learned and recited, similar to our alphabetical order. I chose to present the vowels in a different order than they appear in the বর্ণমালা (bɔrńômala, “alphabet,” or “garland of letters,” a term developed by ). This is because the order of the vowels is somewhat arbitrary. The order of consonants, however, is anything but arbitrary.

This post will be a little bit of a ramble at first. I really want to explain the underlying linguistics enough that you grasp it. This is because there is something very clever that Bengali does with the order of letters, and you might not notice it unless you think carefully about where you’re pronouncing these sounds. But once you realize the pattern, you’ll never forget it. So unlike, say, Greek or Arabic, where you have to just memorize the alphabetical order, you can just think logically and determine which sound comes before which other sounds. It makes using dictionaries sooo easy.

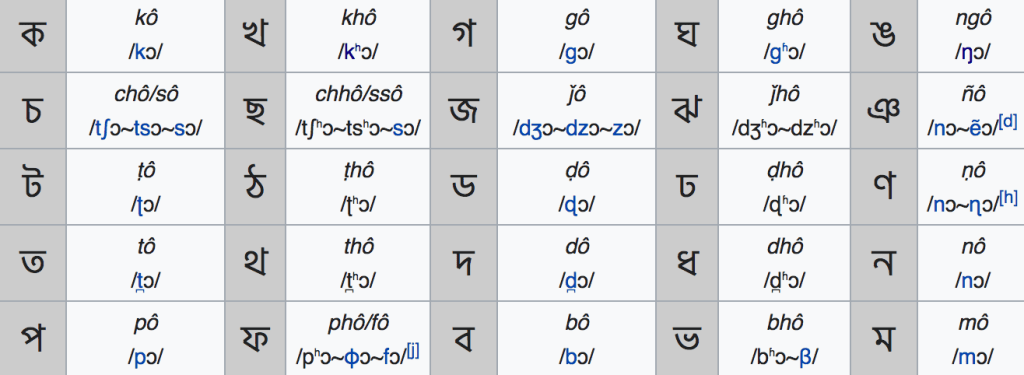

Before we get started, here’s a table of most of the consonants I’ll be covering in this post:

We’ll cover every character here, with the exception of one of the characters in the right hand side of each pair. Most of these are considered special characters and merit their own post.

There is an obvious pattern going on here, in each row of the table, and it’s not hard to recognize. But the cool thing is that the order of the rows also has a nice pattern!

Let’s delve a little into some acoustic phonetics to see why!

Acoustic phonetics is the science of how we produce the sounds of speech: which muscles, organs, and physical processes our body uses to say things out loud. (This is different from auditory phonetics, which studies how we hear and interpret speech sounds)

Consonants are produced by temporarily obstructing the flow of air from the lungs with the tongue, lips, or other articulators. In acoustic phonetics, there are three dimensions to a consonant. Two of these “dimensions” describe how and where the air is obstructed; the third is a little subtler. These three attributes will (almost) determine how the consonant is pronounced – we will see later that Bengali, along with most other Indian languages, adds a fourth dimension to some of these sounds!

Step 1: Manner of articulation

The manner of articulation is the how.

There are two important types of consonants that we’ll be going over today: stops and nasals. These comprise the sounds listed in the table above. We’ll later talk about fricatives and rhotics.

Stops (aka occlusives, plosives) are produced by entirely blocking the flow of air from the lungs through the vocal tract. As air flows up through the vocal tract, it is trapped by the articulators (this is called occlusion), which creates pressure. The consonant itself is produced by releasing this pressure (this is called plosion).

If that seems complicated, just notice that English is full of stops. The sounds “B, P, T, D, K, and hard G” are all stops. Try pronouncing a few of these, going very slowly, and see if you can feel the occlusion and plosion happening!

Nasals are a lot like stops (In fact they’re also sometimes called nasal stops). The main difference is that airflow is not completely blocked for a nasal consonant – some of the air escapes through the nose!

English, again, is full of nasals. The obvious ones are “M, N” – but there is a third nasal that we use all the time without realizing, which we write as [ŋ] in the IPA. This is the “ng” sound in words like “king” and “bank.” Try pronouncing each of these, hold your hand in front of your face, and see if you can feel the breath escaping your nose!

Lastly, Fricatives are created by causing turbulence, or chaotic airflow, by bringing our articulators close enough to increase the pressure of airflow without fully obstructing it. English is once again full of these: the sounds “F, V, S, Z, SH, ZH, and H” are all fricatives.

Step 2: Place of articulation

The place of articulation is the “where.”

This isn’t so hard to understand – consonants sound different when we use our lips instead of our tongue to produce them, or when we move our tongue to a different part of the mouth. The tricky part is that linguists use fancy terms for the different places and parts of the vocal tract.

- The stops “P” and “B,” and the nasal “M,” are called bilabial, from bi (two) + labia (lip). They’re formed by pressing both lips together – the place of articulation is right at the front of the mouth, between the lips.

- Further back in the mouth, the stops “T” and “D” and the nasal “N” are dental. This means the tongue stops the air by making contact with the teeth. NB that most English speakers actually pronounce these as alveolar – the tongue is on the alveolar ridge, the little bump of bone right behind the teeth.

- In Bangla there are true dentals, pronounced right at the teeth, much like the “t” sound in Spanish. But there are also retroflex (or alveolar) stops. These are pronounced with the tongue curled back, so that the tip of the tongue touches the roof of the mouth: retro (backward) + flex (curl). Retroflex sounds are a very famous feature of Indian languages – ask an English-speaker to do a stereotypical Indian accent, and they will likely use these sounds.

- Even further back, the stops “K” and “G” and the nasal “ŋ” are velar. The back of the tongue makes contact with the velum, aka the soft palate. If you feel the roof of your mouth, you’ll notice that the front part right behind the teeth is hard and boney – this is the (hard) palate – but further back, the bone ends and there’s a squishy soft spot. This is the velum.

(Bengali doesn’t really have palatal consonants. But it formally does – they’re just pronounced as affricates. This is when a consonant is released with a bit of a “fricative ending.” The two affricates in English are “CH and J.” Sanskrit and Early Bangla probably had the palatal stops [c] and [ɟ], but these later evolved into the alveolar affricates [t͡ʃ] and [d͡ʒ], pronounced like English “CH” and “J”)

(Stop. At this point, go back up to the table above. Can you spot the pattern already??)

Step 3: Voicing

Voicing is our second-to-last “dimension” of consonants. It’s also the last dimension we’d need to describe all the consonants in English, but won’t be enough for Bengali. Fortunately, there are only two values it can take: voiced or voiceless!

A consonant is voiced if your vocal chords vibrate while you say it, and voiceless if they don’t move.

The cool thing is, we can feel this vibration really easily!

Hold your hand over your throat. Now make a hissing noise, like a snake: “ssssss…”.

Keeping your hand there, make a buzzing noise, like a bee: “zzzzzz…”.

Feel the difference? Try going “SsssssZzzzzzSsssssZzzzzz” and keep your hand over your throat.

Both the sounds [s] and [z] are dental, and both are fricatives. The only difference between them is that [s] is voiceless while [z] is voiced.

(We name consonant sounds with the following pattern: [voicing] + [place] + [manner]. So for example, [s] is the voiceless dental fricative.)

Step 4: Aspiration

This is the secret fourth dimension that Indian languages have. The distinction between aspirated and plain consonants is hard for English speakers to master – about as hard as the distinction between dental and alveolar.

An aspirated consonant is released with turbulent airflow from the glottis – or a little “puff of air,” if you will. A plain consonant is just un-aspirated.

The tricky thing is that we use both of these in English, but don’t distinguish them. Here’s an experiment you can do to see the difference.

Hold your hand directly in front of your lips and say the word “tar.” Notice the slight burst of air that follows the “T” sound at the beginning. Now keeping your hand there, say the word “star.”

Did you still feel that burst of air?

Chances are, you didn’t. That’s because the aspirated consonant [th] is an allophone of the plain consonant [t], in most dialects of English. The aspirated consonant is what we usually use, but the plain consonant occurs in consonant clusters (although I’ve met English-speakers who use the aspirated sound everywhere).

Just for good measure, do the same thing for “par” and “spar,” and for “car” and “scar.” Try to really isolate the un-aspirated version of each phoneme: pronounce it by itself, or followed by a vowel, and see if you can produce both sounds. If you’re feeling up for it, try to do the same with the affricates ch [t͡ʃ] and j [d͡ʒ]. Try to do it again with all the voiced stops [b], [d], [g]!

Step 5: The Pattern

Okay, now we’re ready.

Here’s an explanation of the pattern I promised!

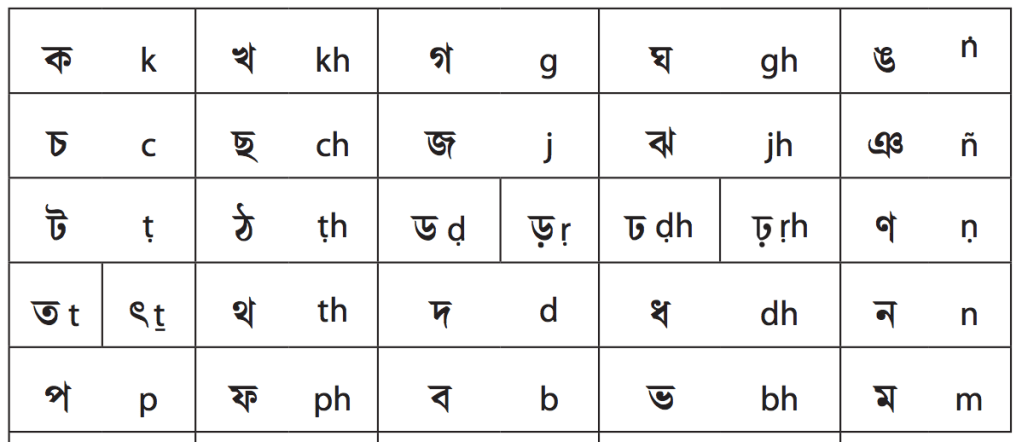

Let’s take a look at the bɔrńômala again and apply our newfound linguistic insight:

Can you see the pattern?

The consonants are moving forward in the mouth!

The first row of consonants consists entirely of velar sounds. The next row is the palatal sounds (although we know these are really affricates). Then retroflex, then dental, and finally, bilabial.

Each row’s sounds are further down the vocal tract than the row before it!

See what I mean with this diagram of the vocal tract:

The rows correspond to the numbers 8 (bilabial), 7 (palatal/affricate), 6 (retroflex), 3 (dental) and 2 (bilabial). Notice how these numbers decrease – they move forward towards the lips!

Here’s the full pattern, that you can use to decide whether a consonant comes before or after another consonant. It’s based on a heirarchy – each “level” overrules the level directly after it.

- Level 1: Place of Articulation – Consonants that are further back in the mouth come before consonants that are further forward in the mouth. This determines the rows of consonants and their order

- Level 2: Manner of Articulation – In each row, stops come before nasals. The nasal sound is always at the end of the row.

- Level 3: Voicing – In each row, voiceless consonants come before voiced consonants.

- Level 4: Aspiration – In each row, plain consonants come before their aspirated counterparts.

NB: Everything from this section on goes into a lot more detail than is probably necessary. If you’re looking for a quick guide to the remaining consonants, just skim this stuff and figure out a way to pronounce things that works for you – don’t get caught up on trying to master unusual phonemes. If you’re learning Bangla, all that matters is that you can say, and hear the difference between aspirated and plain, and between retroflex and dental.

Step 6: Some notes on usage and pronunciation

Although the character ফ (ph) technically represents the aspirated voiceless bilabial stop [ph], it isn’t pronounced that way in most dialects. Instead it’s pronounced as [ɸ]. This sound is very similar to the “F” sound [f] that appears in English. But [f] is labiodental, meaning the lip touches the teeth, whereas [ɸ] is bilabial, meaning that both lips are used to create turbulence. This sound is best described as somewhere between an “F” and a “W.” If you’re learning Bangla, just pronounce it as [f] – nobody will notice.

Those nasals aren’t what they seem to be either. Sanskrit might have had the retroflex nasal ণ [ɳ] and the palatal nasal ঞ [ɲ], but both of these are pronounced as [n] in Bangla. In fact, the palatal nasal ঞ is never used on its own in Bangla. It only appears as part of conjunct characters – something we’ll talk about later in this article, and cover in more depth in another post.

Step 7: What’s left over

There are a few more standard characters that need to be included, before we move on to special characters and conjuncts.

I haven’t addressed the fricative sounds in Bangla. There aren’t many of them but unfortunately there are multiple characters that all represent the same sound – all three are pronounced as the English “shhh” sound that occurs in “ship,” but are transcribed differently:

- স – s

- শ – sh

- ষ – ś

The reason for this is again that these sounds were all distinct in Sanskrit. Sanskrit probably had three voiceless fricatives:

- a dental [s] as in “kiss,” written স

- an alveolar [ʃ] as in “fish” (or possibly retroflex [ʂ]), written শ

- a palatal [ɕ], written ষ

The second two sounds merged into [ʃ], and now [s] has more or less merged with them as well. The only exception is that it’s still pronounced [s] before a dental consonant:

স্নান [snan] - "shower"

স্থান [sthan] - "place"

আস্তে [aste] - "slow"

There are also three rhotic sounds (“R”-like sounds), that have also merged to some extent in many dialects.

- র – r

- ড় – ṛ

- ঢ় – ṛh

The first sound is probably the most common, and is an alveolar tap, [ɾ]. This sound is used in many dialects of American English in words like “water” [waɾ] and “ladder” [læɾ].

The second sound is the retroflex version of this, [ɽ]. The final sound is the aspirated version of the retroflex version: [ɽh]. Many dialects of Bengali, including the dialects of Kolkata, preserve the two sounds [ɽ] and [ɾ] as separate; but many others, including the dialects of Dhaka, merge them into [ɾ].

The remaining characters are thankfully pretty straightforward:

- ল – l

- য – j

- য় – y

- হ – h

The only note I have about any of these is that sometimes য় (y) can be combined with ও (o) to create a “W” sound, which appears a lot in Bangla but doesn’t have its own character:

দেওয়াল [dewal] - "wall"

ওয়ারী [warī] - "Wari" (district of Dhaka)

Also, since Bangla doesn’t natively have any voiced consonants, the characters জ and য are used to represent the voiced dental fricative [z] in loanwords (from English, Persian, Arabic and other languages).

Step 8: The End/শেষ

I hope this was a very thorough, insightful guide into how to use the table of characters and the dictionary at the back of your textbook.

I’ve gone over consonants and vowels, so there can’t be any more left to say, right…

Wrong.

There’s a whole lot of weird characters I haven’t gotten to yet. Half of these are special characters. Some of these are variant forms of the consonants or vowels given here which are only use in special environments, like in the end of a syllable. Others are leftovers from Sanskrit, which often aren’t pronounced at all, but affect the spelling of a word.

Then there are markers and diacritics. These are usually used to write consonant clusters – you can sometimes turn the first or second consonant into a tiny “decoration” on the other, which helps save space. Many consonants have a special diacritic that can be used in every environment, and these are worth learning.

Finally, there are conjunct characters, the bane of my existence, which still often confuse me. These are again used to write consonant clusters. They differ from markers/diacritics because they can be very irregular and require memorization. But once again there is logic and patterns that make them slightly easier to learn.

If you’re feeling terrified, don’t give up hope just yet! Like I said, this can all be learned, on a piece-by piece basis, and I’m here to walk you through it!